Statistics and interactive maps tracking turnout and registration in the 2020 elections, including analysis of how city elections changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Voter Analysis Report for 2020-2021(released April 30, 2021) includes comprehensive analysis of the 2020 presidential election year, conducted during a once-in-a-century pandemic and policy recommendations to expand access to voting and improve future NYC elections. The tabs on this page include an executive summary and interactive maps, providing additional context for the full PDF report.

For the best experience, please view maps using Chrome or Internet Explorer. Users may experience issues with interactive maps in Mozilla Firefox.

2020 Election Overview

The 2020 election year was dominated by media coverage of the presidential race and mitigating the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. For the most part, elected officials and election administrators rose to the occasion and New York City voters were resilient and found a way to safely vote in spite of these challenges.

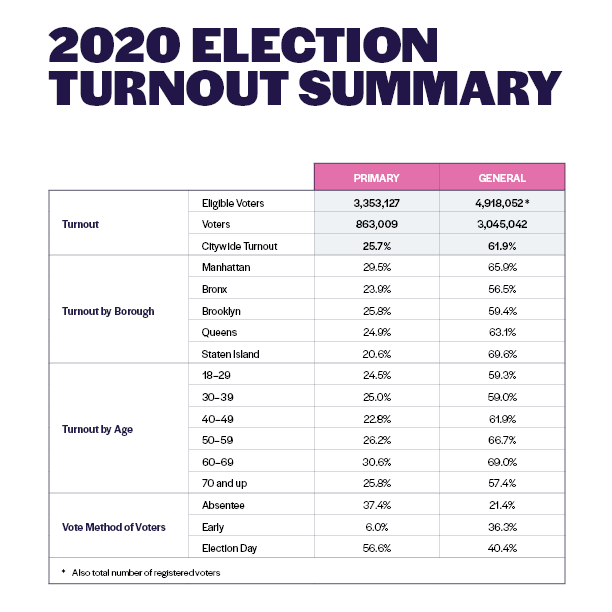

For the first time ever, all voters were able to vote by three ways: by mail, early in person, or on Election Day.

- Absentee voting, or vote by mail, was popular in the primary and general elections: 37.4% of primary election voters and 21.4% of general election voters returned absentee ballots, compared to 2.6% of voters who returned absentee ballots in the 2019 general election.

- Early voting was popular in the general election: 36.3% of general election voters early voted, compared to 7.6% of general election voters in 2019.

- Election Day voting saw its lowest vote method percentage ever with only 56.6% of primary election voters and 40.4% of general election voters choosing to vote in person on Election Day.

Staten Island, which had the lowest voter turnout in the primary election (20.6%), turned out to vote at a high rate in the general election, at almost 70.0%. Turnout disparity can still be seen from a community district level, where the turnout difference between the highest and lowest turnout community districts continues to be about 25.0% in both the primary and the general elections.

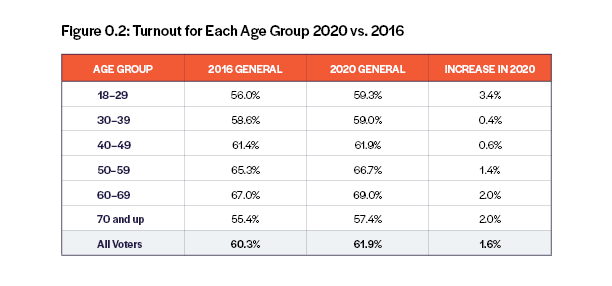

In presidential election years, voters aged 18 to 29 generally have higher turnout than they do in non-presidential years; in 2020 we also saw an increase in voter turnout compared to the last presidential year. Turnout for this age group increased by 3.4% from the 2016 to the 2020 general election. The youth turnout trend was observable across the entire country, with total national youth turnout estimated to be between 52% to 55% percent nationwide, an increase of about 8% compared to 2016. Total turnout in the 2020 general was 61.9%, representing a slight increase of 1.6% over 2016’s turnout of 60.3%.

Analysis: Who is early voting?

The 2020 general election was the second general election cycle with early voting available, which allowed us to look more closely at the characteristics of voters who vote early, using information readily available in the City’s voter file.

We found that young voters are just as likely as other voters to vote early, and widespread voter education efforts to encourage early voting in the general election paid dividends for all age groups. The average age of primary 2020 early voters was 52, compared to the overall voter average age of 51. In the general election, the average age of early voters was 49, compared to the overall voter age of 48.

A person who votes early once is extremely likely to continue doing so. We found that people who voted early in 2019 were more likely to vote early in the 2020 primary and general elections than people who had not yet voted early. If a voter voted early in at least one previous election, they were 372% more likely to vote early in the 2020 general.

We will continue to perform additional analysis of the characteristics of early voters and what might drive them to vote early versus on Election Day or by absentee.

How we responded to COVID-19

We entered 2020 expecting it to be an historic election year in terms of voter turnout, with a highly anticipated presidential election following several years of increasing voter turnout. Like many doing voter engagement across the city, our previous work was heavily reliant on in-person organizing. Our plans were quickly disrupted by COVID-19 which made it unsafe to conduct in-person activities and also drove uncertainty around election dates and voting methods. In short order, we had to pivot our strategy to adapt to the circumstances of the pandemic.

Some of the things we changed this year:

- We shifted to a digital model of communications and outreach, reaching voters through online methods and deploying new tools for voter engagement, such as peer-to-peer texting.

- We worked with our counterparts at DemocracyNYC in the Mayor’s Office to launch a consortium effort to bring together partners across government, civic space, and communities across New

- York City on weekly virtual calls.

- We directed voters away from Election Day voting and to newly available and safer voting methods. In the primary election, we encouraged voters to request an absentee ballot and to vote absentee. In the general election, we highlighted and heavily promoted early voting.

- We created a TurboVote website to combat the decrease in new voter registrations

- We set up a successful model of youth engagement through peer-to-peer style education, partnership with CUNY, and We Power NYC Ambassadors.

- We held virtual Voter Assistance Advisory Committee hearings which had record attendance and participation, allowing us to hear from more New York City voters.

Election year 2020 pressure-tested elections administration in New York State and New York City while also providing more ways to vote than ever before. Our policy recommendations focus on making improvements to flawed existing procedures that were laid bare in 2020, in some cases because it was the first time to be tested on such a massive scale and proved inadequate to the emergency measures that needed to be taken. Our legislative recommendations focus on continuing the important work begun by the State government in 2019 to modernize New York State Election Law.

Elections Administration and Data Transparency

- Report the return and canvass of absentee ballots in a manner consistent with other unofficial election results.

- Provide election results in machine-readable format (.csv or .xls) and broken down into every political subdivision that exists at the local level.

- Publish other elections data that would allow government agencies, non-profits, and other community groups to tailor and target their voter education and outreach efforts.

- Use internal data to provide greater customer service to voters, such as providing line wait estimates.

Voter Registration

- Amend the Election Law to streamline the three voter registration deadlines — change of enrollment, new registration, change of address — into one consistent deadline.

- Pass Same Day Voter Registration for the second time, allowing the Constitutional amendment to be put to voters in November 2021.

Absentee Voting

- Amend the Election Law to permanently allow electronic, phone, fax, and email applications for absentee ballots.

- Push daily updates to the voter-facing absentee tracking portal, to reflect when returned ballots arrive at the Board of Elections office.

- Expand the locations of absentee drop boxes to schools, libraries, and other common locations where voters could conveniently drop off ballots prior to early voting or Election Day.

- Amend the Election Law to cover return postage on absentee ballots in the State budget.

- Provide detailed summary breakdowns of absentee ballot invalid codes so that voter outreach campaigns can be tailored to educate absentee voters.

- Pass No Excuse Absentee voting for the second time, allowing the Constitutional amendment to be put to voters in November 2021.

Early Voting

- Designate more early voting locations to alleviate long lines during early voting.

- Implement voter centers to allow voters more convenience and flexibility, while also potentially alleviating long lines.

- Compel sites to be used as poll sites, particularly those who receive significant tax breaks or grant funding from the city or state.

- Standardize and lengthen early voting hours, particularly on weekends, to reduce confusion and provide enough hours to accommodate voters.

- Ensure proper resource allocation, such as the number of early voting and Election Day workers and the number of check-in desks, by using internal Board of Elections data.

Expanding Access to the Polls: Voters with Disabilities

- Create a specific Voter Assistance Hotline for voters with disabilities to call and request information and materials in the accessible format that is best suited for them.

- Engage a cross-section of non-profit and community groups that serve the disability community through a Voting Accessibility Advisory Committee to help review and rate the next Ballot Marking Device (BMD) voting machine provider.

Expanding Access to the Polls: Voters with Limited English Proficiency

- Create a specific Voter Assistance Hotline for voters with limited English proficiency to call and request information and materials in the language that is best suited for them.

- Create a formal Language Accessibility Advisory Committee modeled after the one that exists in Los Angeles County to ensure best practices are being followed in translation of materials.

- The CFB commits to following the guidelines presented in the City’s language access plan and providing its commonly distributed materials in all the designated citywide languages as soon as practicable.

- Expanding Access to the Polls: Rights Restoration for Voters who are on Parole or Probation, or Incarcerated

- Consider legislation to strike the part of the Election Law which takes away the right to vote for those convicted of felonies.

- Ensure that all New Yorkers, regardless of parolee, probation, or carceral status, have the right to vote.

Primary Election 2020

General Election 2020

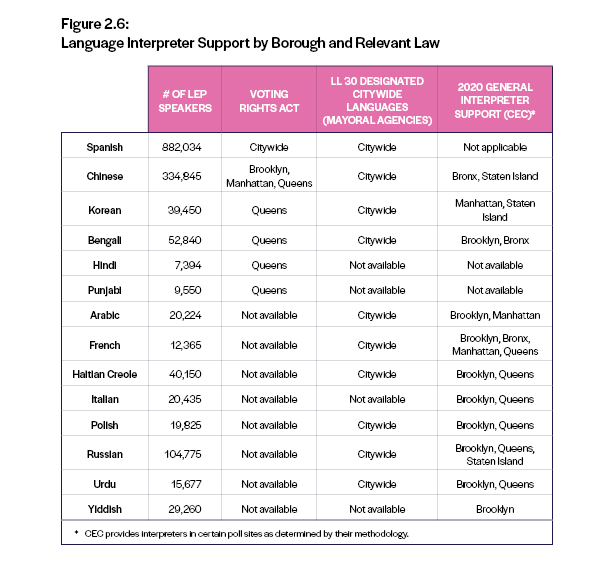

In New York City, 858,385 citizens of voting age population are Limited English Proficiency (LEP), defined by the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey as speaking English less than very well.[i] Research indicates that major public institutions, including healthcare and education systems, are ill-equipped to accommodate the needs of people with LEP.[ii] This leads to larger barriers LEP speakers face when trying to understand and access the services they need when navigating these systems.[iii] Access to the ballot for LEP individuals has grown over time but has ample room for improvement.

Section 203 of the Federal Voting Rights Act (VRA) requires counties to provide translation and interpretation services to large populations of Asian, Native American, and Alaskan Native language speakers as well as Spanish speakers if there are more than 10,000 speakers of a language or the community makes up over 5% of that county’s population. This measure tries to combat the history of exclusion of those communities from the political process.

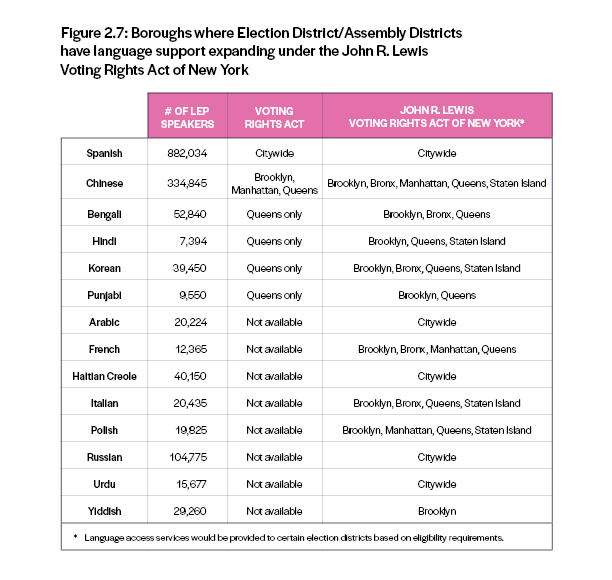

In accordance with Section 203 of the federal VRA, the City BOE serves Spanish, Bengali, Chinese, and Korean speaking communities with translated voting materials and interpreters in certain election districts within certain boroughs. They also serve Hindi speaking communities in Queens with interpreters and try to hire Hindi interpreters who also speak Punjabi when possible. However, out of 1.7 million limited English proficiency (LEP) speakers in New York City, over 300,000 do not have access to election materials in their native languages, because they speak a language not covered by the VRA.[iv]

Other city agencies have stepped in to provide additional language access support. During the November 2020 general election, the Civic Engagement Commission (CEC) provided interpreters in Arabic, Bengali, Cantonese, Mandarin, French, Haitian Creole, Italian, Korean, Polish, Russian, Urdu, and Yiddish at 100 poll sites around the city.[v] The CFB’s website hosts voter registration forms translated by the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs in Albanian, Arabic, French, Greek, Haitian Creole, Italian, Polish, Russian, Tagalog, Urdu, and Yiddish in addition to the forms provided by the City BOE in the four VRA languages.

Translated registration forms may help LEP voters get registered but those voters may not feel comfortable casting their vote without support in their preferred language. Additionally, CEC interpreters were only available at select locations and on three out of the total ten days for early voting and Election Day. This patchwork of policies does not ensure a uniform level of service for LEP voters. Support for LEP voters in New York City should be consistent throughout the voting process and include targeted outreach to ensure LEP communities know where and how to access these translated resources.

Local Law 30-2017 requires agencies that provide direct services to the public to translate widely disseminated materials in the ten designated citywide languages. However, the City BOE does not fall under this requirement since it is governed by New York State Election Law and constituted under the New York State Constitution.[vi] For this reason, passing state legislation is the most effective way to ensure that voters have consistent access to translation and interpretation services throughout the voting process.

Recently, Senator Zellnor Myrie introduced the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act of New York, which contains a section that seeks to improve assistance for language-minority groups.[vii] If over 2% of voting-age citizens, or over 4,000 voting-age citizens, in an election district speak English “less than very well” and speak the same language, the BOE is required to provide translation and interpretation services in that language. The bill specifies that notices, registration forms, instructions, assistance, and ballots must be available in that language as well as any materials relating to the electoral process. For languages that are oral, unwritten, or historically unwritten, the bill allows the BOE to provide only verbal information and assistance.[viii]

As shown in Figure 2.7, language support would significantly expand under the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Act of New York. The map in Figure 2.8 illustrates which election districts would provide voters with more language support if this bill becomes law. As shown, Russian and Haitian Creole speakers, the two most widely spoken languages in New York City that are not covered by the VRA, serve to benefit the most from this bill. The other designated citywide languages (Arabic, French, Polish, and Urdu) also would be covered.

As stated in testimony provided to the State Senate Elections Committee in March 2020, NYC Votes strongly supports passage of the John Lewis Voting Rights Act of New York, as these changes will benefit communities across the City that currently do not receive the voting services they need and deserve.[ix] Providing interpretation services and translating election materials into more languages for underrepresented groups is essential to increasing participation in our democracy.

However, it is not enough for the Voting Rights Act of New York to require the City BOE to provide interpreters and translations. These services must also be accurate, reliable, accessible, and easy to understand. The Department of Justice has identified accurate translations as a key to a successful language access program, as poor translations can mislead voters. In order to ensure that translated voting materials are helpful for voters, the BOE should create a Language Accessibility Advisory Committee modeled after the one that exists in Los Angeles County. Their Advisory Committee is made up of non-profit and community groups whose memberships include LEP voters. Their role is “providing expertise on reviewing election materials in the identified languages” as well as promoting translated material and giving feedback on interpreters and translation services.[x]

The BOE should also implement best practices when incorporating new language support by using the dialects understood by voters in the city and rely on plain language to include as many low-literacy voters as possible. The Center for Civic Design, through their language access research, has created a guide for interested jurisdictions to follow when incorporating more languages into their voting materials. The organization recommends maintaining a consistent layout and using visuals to indicate different languages. These guidelines guarantee that voters are easily able to find the language they prefer and understand the translation when they read it.

Though these recommendations maximize usability, they present a real challenge to the City BOE for disseminating information to the hundreds of thousands of additional voters who would be covered under the bill. In addition to hosting translated materials on their website, the Board should implement a Voter Assistance Hotline similar to the system already in place in Los Angeles County to ensure they are able to reach LEP voters from multiple angles. With a Voter Assistance Hotline, the City BOE would be able to fulfill requests from voters for printed translated election materials without having to mail these materials across the city. Akin to how the hotline operates in Los Angeles County, this number can also serve as the space where voters can hear about registration and voting information in the language of their choice.

As stated before, the City BOE is not required to produce its voting materials in the ten citywide languages. Neither is the CFB. As an independent board, we do not fall under the category of mayoral agency designated by Local Law 30 of 2017. However, we recognize that if voters are to receive translation and interpretation services at every step of the voting process, NYC Votes must also be included. In the best interest of voters, we commit to following the guidelines presented in the City’s language access plan and providing its commonly distributed materials in all the designated citywide languages as soon as practicable.[xi]

[i] U.S. Census Bureau. 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=limited%20english%20speaking&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B16003&hidePreview=true

[ii] R.S. Guglielmi. Native language proficiency, English literacy, academic achievement, and occupational attainment in limited-English-proficient students: A latent growth modeling perspective. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 322-342. 2004. http://jimelwood.net/students/grips/tables_figures/latent_growth_figure_example.pdf

[iii] Shi, Lebrun, and Tsai. The Influence of English Proficiency on Access to Care. Ethnicity & Health, 14(6), 625–642. December 18, 2008. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-primary-care-policy-center/Publications_PDFs/2009%20EH.pdf

[iv] U.S. Census Bureau. 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=limited%20english%20speaking&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B16003&hidePreview=true

[v] New York City Civic Engagement Commission. "Poll Language Assistance List.” https://www1.nyc.gov/site/civicengagement/voting/poll-site-language-assistance-list.page

[vi] N.Y. City Charter § 23-1102

[vii] New York State Senate S7528. (2020). https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/s7528/amendment/original

New York State Assembly A10841 (2020) https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2019/a10841/amendment/original

[viii] This bill is different from the federal John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. In 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a Voting Rights Advancement Act in order to restore the protections of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, parts of which were struck down by the Supreme Court in 2013. When the same bill was introduced in the U.S. Senate, it was renamed the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. If passed, the bill would try to fight voter suppression laws around the country. For language access, this means the federal government would review state laws that aimed to reduce multilingual voting materials. It does not change anything about Section 203 of the Voting Rights Act, the section outlining the requirements jurisdictions must follow when providing translation and interpretation services.

[ix] Testimony of Eric Friedman before the New York State Senate Elections Committee. March 3, 2020. https://nyccfb.info/media/testimony/testimony-of-eric-friedman-assistant-executive-director-for-public-affairs-to-the-new-york-city-campaign-finance-board-to-the-new-york-state-senate-elections-committee/

[x] LA County Registrar Recorder and County Clerk. “Language Accessibility Advisory Committee.” https://www.lavote.net/home/voting-elections/community-voter-outreach/language-accessibility-advisory-committee

[xi] To accomplish this goal, the CFB will request a special data set from the Census Bureau with data on LEP speakers broken down by election district. With this data set, we can better understand the impact of changes to voting and develop more accurate recommendations in the future.